C# Generics and Unity

/Generics are something that can sound scary, look scary, but you are probably already using them - even if your don’t know it.

So let’s talk about them. Let’s try to make them a little less scary and hopefully add another tool to your programmer toolbox.

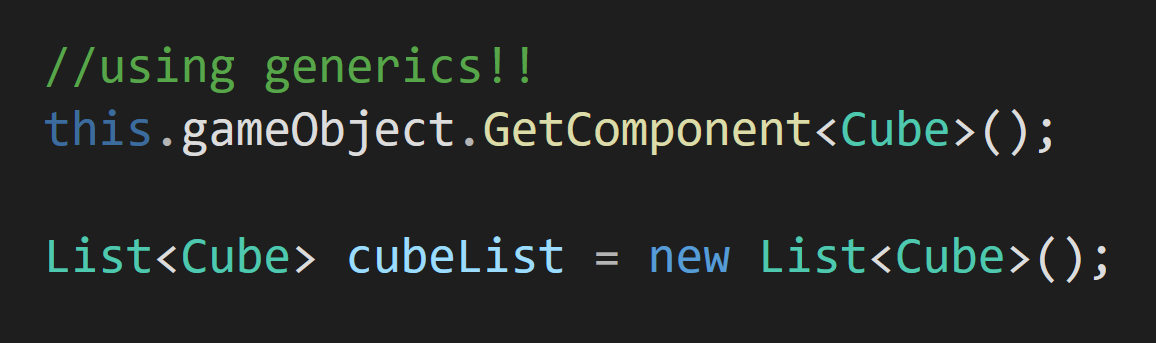

If you’ve used Unity for any amount of time you’ve likely used the Get Component function. I know when I first saw this I simply accepted the fact that this function required some extra info inside of angle brackets. I didn’t think much about it.

Later I learned to use lists that had a similar requirement. I didn’t question why the type that was being stored in the list needed to be added so differently compared to when creating other objects. It just worked and I went with it.

It turns out that those objects are taking in what’s called a generic argument - that’s what’s inside the angle brackets. This argument is a type and it helps the object know what to do. In terms of the GetComponent function, it tells it which type to look for and with the list, it tells the list what type of thing will be stored inside that list.

Generics are just placeholder types that can be any type or they can also be constrained in various ways. It turns out this is pretty useful.

Why?

Ok. Great. But why would you want to use generics?

Well essentially, they allow us to create code that is more general (even generic) so that it can be used and reused. Generics can help prevent the need for duplicate code - which for me is always a good thing. The less code I have to write, the less code I have to debug, and the faster my project gets finished.

We can see this with the GetComponent function in that it works for ANY and ALL types of monobehaviours. This one function can be used to find all built-in types or types created by a programmer. It would be a real pain if with each new monobehaviour you had to write a custom GetComponent function!

The same is true with lists. They can hold ANY type of object and when you create a new type you don’t have to create a new version of the list class to contain it.

So yeah. Generics can reduce how much code needs to get written and that’s why we use them!

Ok. So Give Me An Example!

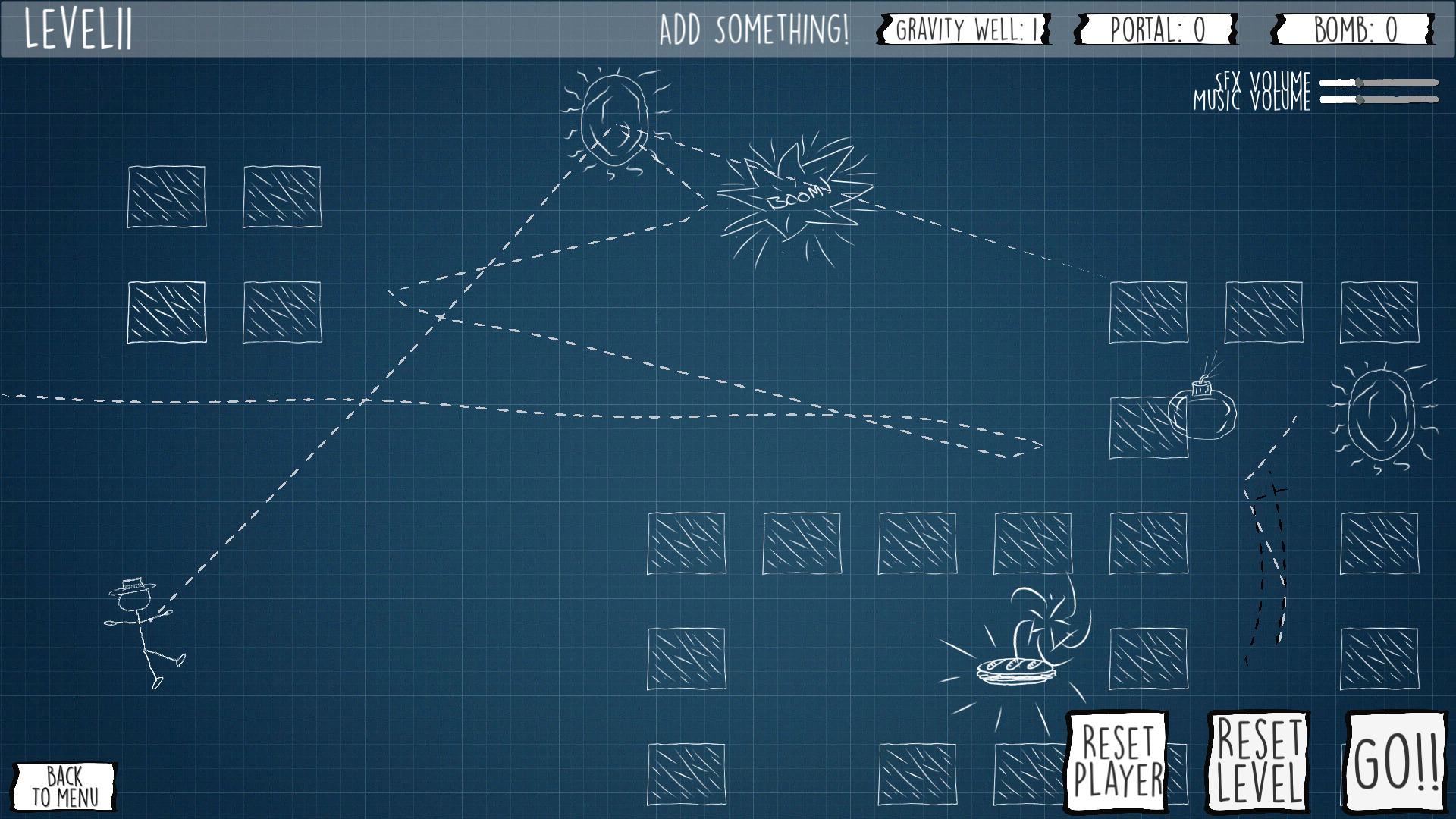

I’ve created a simple scene of various shapes. I’ve created some code that will generate a grid of random shapes… but that’s not the important part.

The important part is that I have four classes defined. The first is a basic shape class that the cube, sphere, and capsule class inherit from. Then each of the prefab shapes has the correspondingly named class attached to them.

Not much going on here!

All of these classes are empty and are primarily used to add a type to the prefab. I do this fairly often in my projects as it’s a way to effectively create tagged objects without using the weakly typed tag system built into Unity. I find that it’s an easy and convenient way to get a handle on scene objects in code.

But more to the point! It allows us to leverage generics in C# and Unity.

When the shape objects are instantiated they are all added to a list that holds the type “shape" as a way of keeping track of what’s currently in the scene. Instead of just shapes sitting in a grid, these could be objects in a player’s inventory or maybe a bunch of NPCs that populate a given scene or whatever.

You can imagine 2 more exactly like this… Just with “Capsule” or “Sphere” instead of “Cube”

So let’s imagine you need to find all the cubes in the scene. That’s not too hard you could write a function like the one to the right. We can simply iterate through the list of scene objects and add all the cubes to a new list and then return that list of cubes.

And then if you need to find all the spheres. We can just copy the find cube function and change the type of list we are returning and the type we are trying to match. Done!

And again we can do the same thing with the capsules.

But now we have three functions that do almost the exact same thing and this should be a red flag! We have three chunks of code doing nearly the exact same thing. There must be a better way?

Turns out there is!

Create A Generic Function

The only difference between the three functions we’ve created is the type! The type in the list and the type that we are trying to match when we iterate through the list.

We are doing the same steps for every type. Which is the exact problem that generics solve!

So let’s make a generic function that will work for any type of shape. We do this by adding a generic argument to the function in the form of an identifier between angle brackets after the function name and before any input parameters.

Traditionally the capital letter T has been used for the generic argument, but you can use anything. It’s even possible to add additional generic arguments. They just need to be separated by commas. Some sources will suggest using T, U, and V which will work but doesn’t necessarily allow for easily readable code. Instead, another convention is to start with a capital T and follow it with a descriptor. For example TValue or TKey. Whatever makes sense for your use case.

This generic argument is the type of thing we are using in our function. Which for our case is also the type stored in the list and is the type we are trying to match. So we can simply replace the particular types with the generic type of T.

Do note that we still have the type of “shape” in our function. This is because the list with all the scene objects is storing types of shape so in this case, that type is not generic.

In my example project, I have UI buttons wired up to call this generic function so that cubes, spheres, and capsules can be highlighted in the scene. Each button calls the same function, but with a different generic argument.

The result? We have less code, the same functionality AND the ability to find new shapes if new types are added to our project without having to create significant code for each type of shape.

Generics Constraints

You may have noticed that I snuck in a little extra unexplained code at the top of our generic function. This extra bit is a constraint. By using the keyword “where” we are telling the compiler that there are some limits to the types that T can be. In this case, we are constraining T to be the type Shape or a type that inherits from Shape. We need to do this otherwise the casting of the object to type T would throw an error as the compiler doesn’t know if the types can be converted.

Constraints can be very wide or very narrow. In my experience, constraints to a parent class, monobehaviour, or component are very common and useful.

Without a constraint, the compiler assumes the type is object which while general there are limits to what can be done with a base object.

For example, maybe you need to destroy objects of a given type throughout your scene. This isn’t too hard to do, but a generic function does this really well.

The function “find all objects of type” returns a Unity Engine Object which is too general. If we constrain T to be a component or a monobehaviour we can then get access to the attached gameObject and destroy it.

(Link) You can find more about constraints here.

Another Example

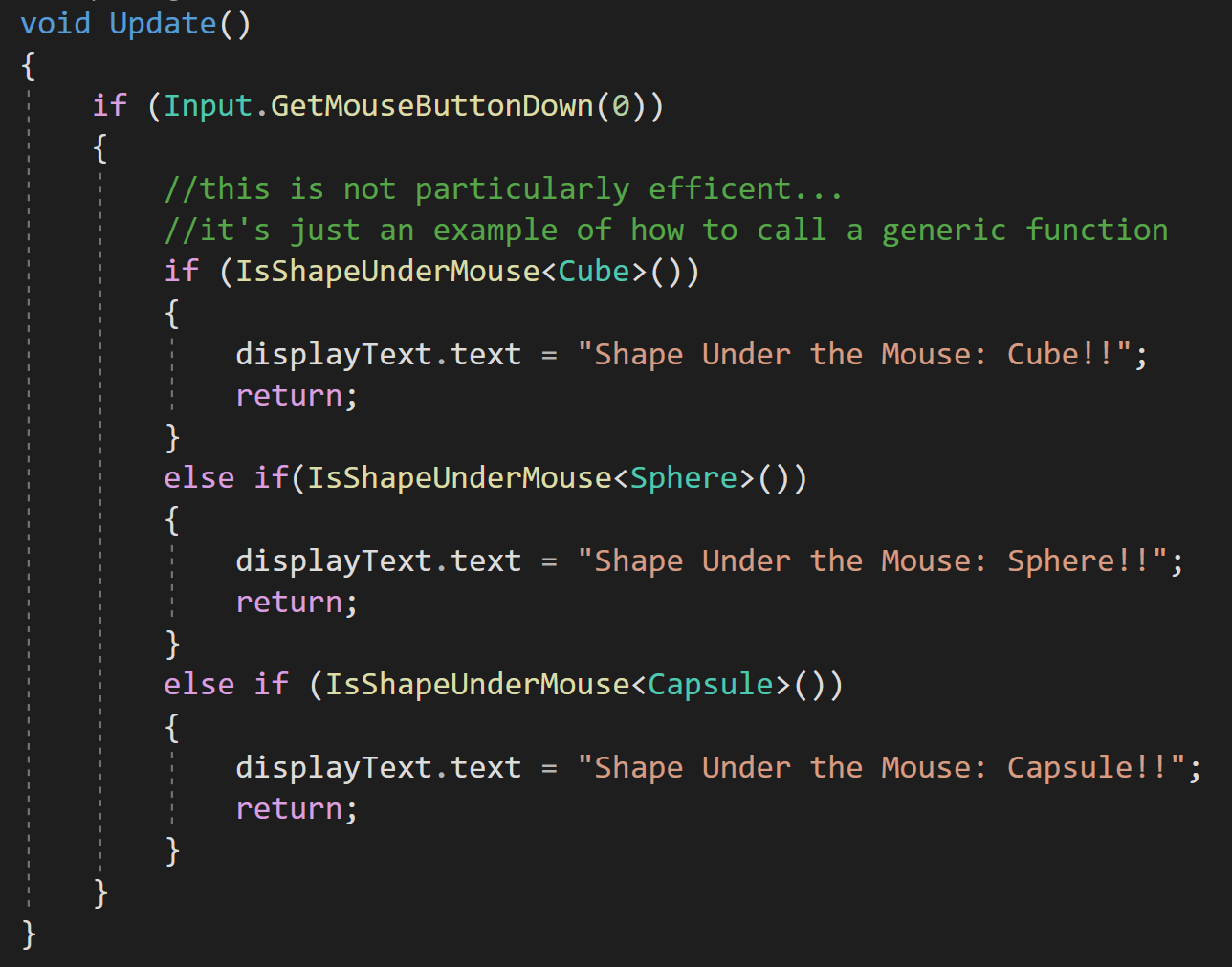

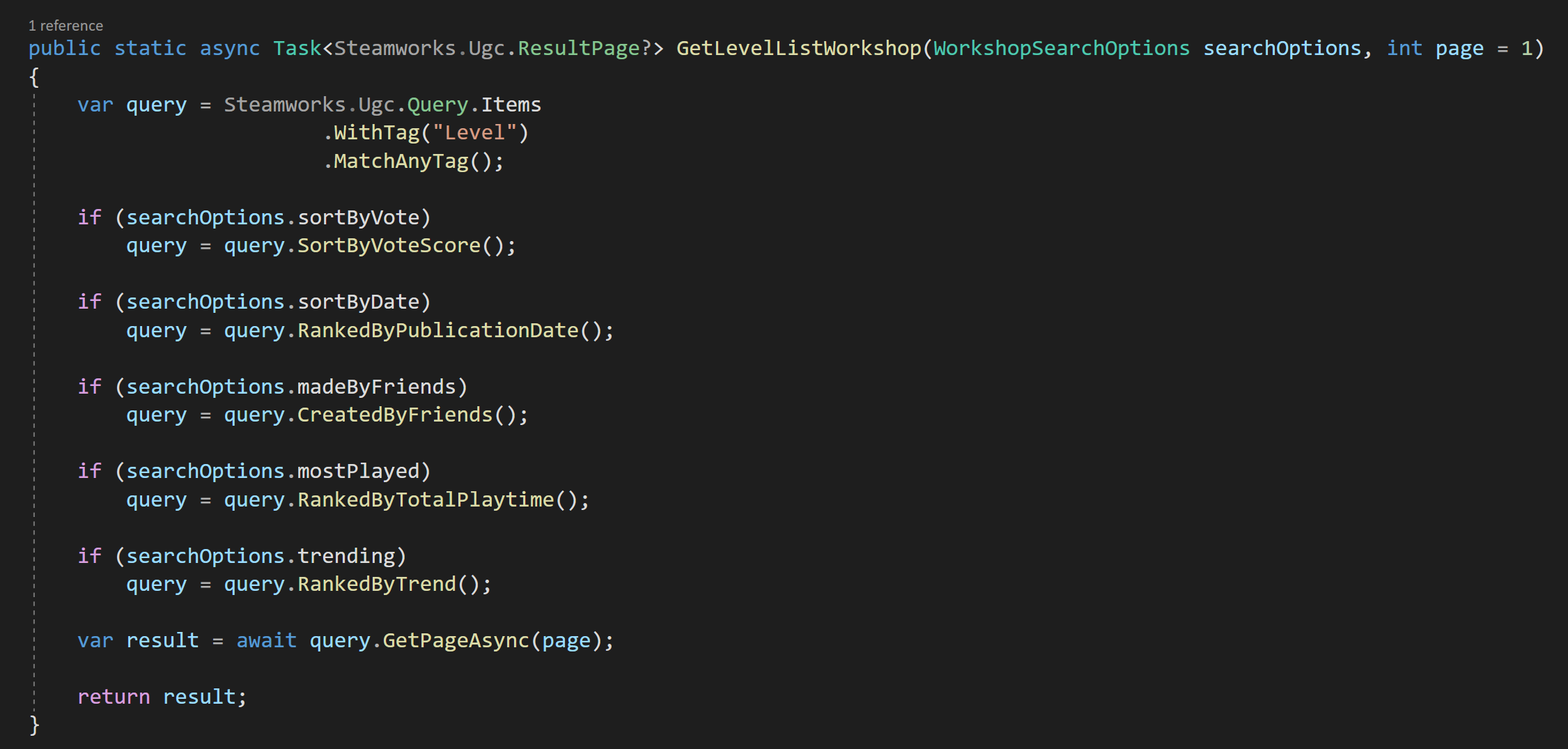

In my personal game project, I often need to check and see if the player clicks on a particular type of object. There are certainly many ways to do this, but for my project, I often just need a true or false value returned if the cursor is hovering over a particular object type.

This is again a perfect use for a generic function. A raycast from the camera to the mouse can return a raycast hit. If that hit isn’t null we can then check to see if the object has a component. Rather than check for a particular component, we can check for a generic type. Note once again we need a constraint and that the generic type needs to be constrained to be a component.

Then to use this function we simply call it like any other function but tell it what type to look for by giving it a generic argument. Not too complex and definitely re-usable.

Static Helper Class

Additionally, many generic functions can also operate as static functions. So to maximize their usefulness, I often place my generic functions in a static class so that they can easily be used throughout the project. This often means even less code duplication!

Generic Classes

So far we’ve looked at generic functions, which I think are by far the most common and most likely use of generics. But we can also make generic classes and even generic interfaces. These operate much the same way that a generic function does.

The image to the right shows a generic class with a single generic argument. It also has a variable of the type T and a function that has an input parameter and a return value of type T. Notice that the type T is defined when the class is created and not with each function. The functions make use of the generic type but do not require a generic argument themselves!

Do note that this class is a monobehaviour and as is Unity will not be able to attach this to a gameObject since the type T is not defined.

However, if an additional class is created that inherits from this generic class and defines the type T then this new additional monobehaviour can be attached to a gameObject and used as a normal monobehaviour.

The uses for generic classes and interfaces highly depend on the project and are not super common. Frankly, it’s difficult to come up with good examples that are reasonably universal.

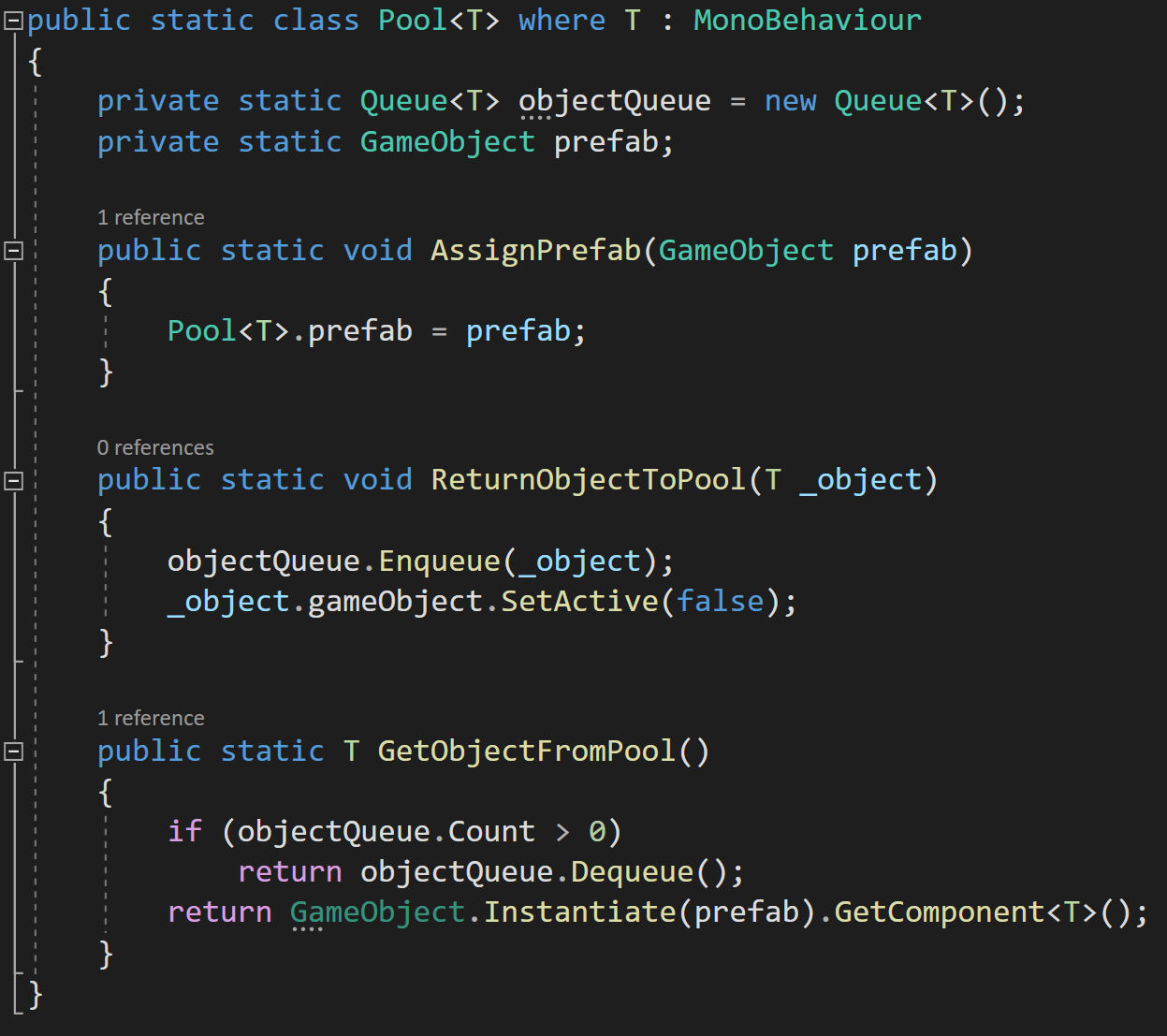

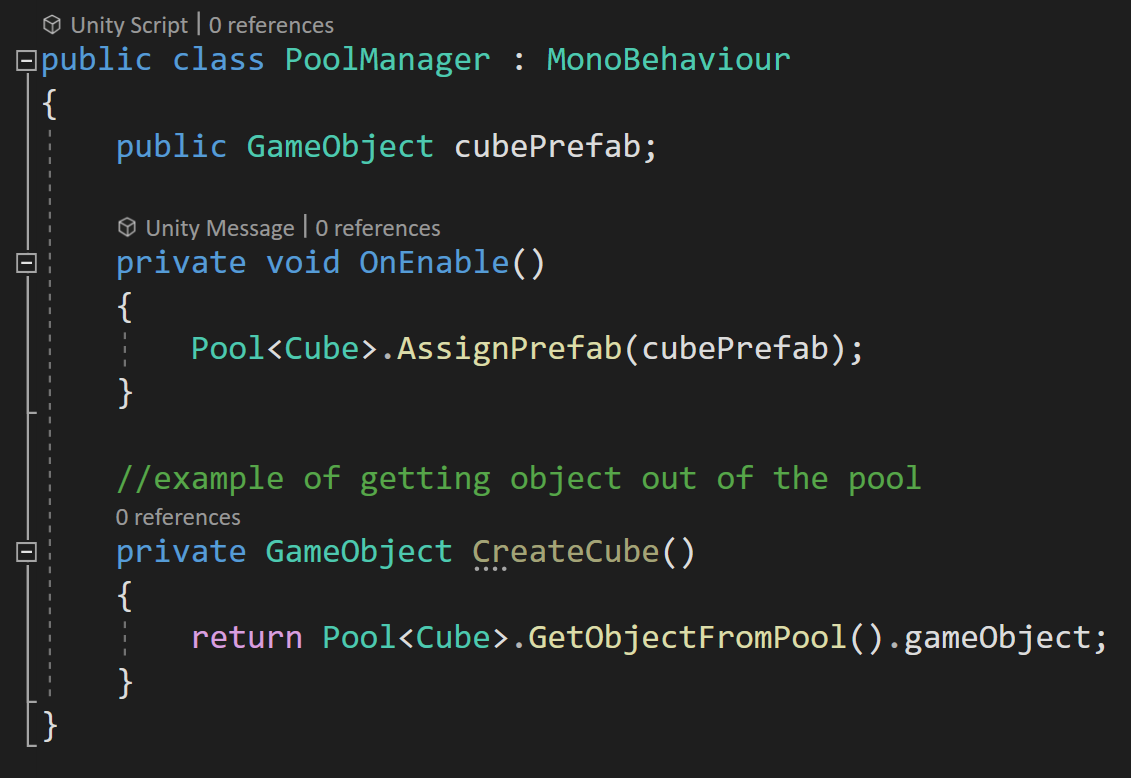

An imperfect example of a generic class might be an object pooling solution where there is a separate pool per type. Inside the pool, there is a queue of type T, a prefab that will get instantiated if there are no objects in the queue plus functions to return objects to the pool as well as get objects from the pool.

The clumsy part here comes from the assigning of the prefab which must be done manually, but this isn’t too high of a price to pay as each pool can be set up in an OnEnable function on some sort of Pool Manager type of object.

This class is static and is per type which makes it easy to get an instance of a given prefab. In this case, we are equating the type with a prefab which could cause problems or confusion, so just something to be aware of.

Generics vs. Inheritance

It turns out that a lot of what can be done with generics can also be done with inheritance and often a bunch of casting. And it might turn out that generics are not the best solution and using inheritance and casting is a better or simpler solution.

But in general, using generics tends to require less casting, tends to be more type-safe, and in some cases (that you are unlikely to see in Unity) can actually perform better.

(Link) To quote a post from Stack Overflow:

You should use generics when you want only the same functionality applied to various types (Add, Remove, Count) and it will be implemented the same way. Inheritance is when you need the same functionality (GetResponse) but want it to be implemented different ways.